An Island In The Moon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''An Island in the Moon'' is the name generally assigned to an untitled, unfinished

''An Island in the Moon'' is the name generally assigned to an untitled, unfinished

Also of interest is that on the last page of the MS are found numerous small pencil drawings of horses, lambs, lions and two human profiles. Additionally, the word "Numeration" has been written in the centre of the page, the word "Lamb" in tiny script between the two human profiles (partly obscured by a large "N"), and two signatures of Blake himself at the top of the page. Also present are various random letters (especially the letter "N") which may be examples of Blake's attempts to master

Also of interest is that on the last page of the MS are found numerous small pencil drawings of horses, lambs, lions and two human profiles. Additionally, the word "Numeration" has been written in the centre of the page, the word "Lamb" in tiny script between the two human profiles (partly obscured by a large "N"), and two signatures of Blake himself at the top of the page. Also present are various random letters (especially the letter "N") which may be examples of Blake's attempts to master

Chapter 1 begins with a promise by the narrator to engage the reader with an analysis of contemporary thought, "but the grand scheme degenerates immediately into nonsensical and ignorant chatter." A major theme in this chapter is that no one listens to anyone else; "Etruscan Column & Inflammable Gass fix'd their eyes on each other, their tongue went in question & answer, but their thoughts were otherwise employed." According to Erdman, "the contrast between appearance and reality in the realm of communication lies at the centre of Blake's satiric method." This chapter also introduces Blake's satiric treatment of the sciences and mathematics; according to Obtuse Angle, "

Chapter 1 begins with a promise by the narrator to engage the reader with an analysis of contemporary thought, "but the grand scheme degenerates immediately into nonsensical and ignorant chatter." A major theme in this chapter is that no one listens to anyone else; "Etruscan Column & Inflammable Gass fix'd their eyes on each other, their tongue went in question & answer, but their thoughts were otherwise employed." According to Erdman, "the contrast between appearance and reality in the realm of communication lies at the centre of Blake's satiric method." This chapter also introduces Blake's satiric treatment of the sciences and mathematics; according to Obtuse Angle, "

''An Island in the Moon''

at the

''Bartleby.com'' article

* ' ttps://archive.today/20130415164216/http://jhmas.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pdf_extract/1/1/41 A Note on William Blake and John Hunter by Jane M. Oppenheimer, '' Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences'', 1:1 (Spring 1946), 41–45 (subscription needed) *

William Blake and the Lunar Society

by William S. Doxey, ''

''An Island in the Moon'' is the name generally assigned to an untitled, unfinished

''An Island in the Moon'' is the name generally assigned to an untitled, unfinished prose

Prose is a form of written or spoken language that follows the natural flow of speech, uses a language's ordinary grammatical structures, or follows the conventions of formal academic writing. It differs from most traditional poetry, where the f ...

satire

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of shaming ...

by William Blake

William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his life, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual art of the Romantic Age. ...

, written in late 1784. Containing early versions of three poems later included in ''Songs of Innocence

''Songs of Innocence and of Experience'' is a collection of illustrated poems by William Blake. It appeared in two phases: a few first copies were printed and Illuminated manuscript, illuminated by Blake himself in 1789; five years later, he b ...

'' (1789) and satirising the "contrived and empty productions of the contemporary culture", ''An Island'' demonstrates Blake's increasing dissatisfaction with convention and his developing interest in prophetic modes of expression. Referred to by William Butler Yeats

William Butler Yeats (13 June 186528 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival and became a pillar of the Irish liter ...

and E. J. Ellis as "Blake's first true symbolic book," it also includes a partial description of Blake's soon-to-be-realised method of illuminated printing

Etching is traditionally the process of using strong acid or mordant to cut into the unprotected parts of a metal surface to create a design in intaglio (incised) in the metal. In modern manufacturing, other chemicals may be used on other types ...

. The piece was unpublished during Blake's lifetime, and survives only in a single manuscript

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand – or, once practical typewriters became available, typewritten – as opposed to mechanically printing, printed or repr ...

copy, residing in the Fitzwilliam Museum

The Fitzwilliam Museum is the art and antiquities museum of the University of Cambridge. It is located on Trumpington Street opposite Fitzwilliam Street in central Cambridge. It was founded in 1816 under the will of Richard FitzWilliam, 7th Vis ...

, in the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

.

Background

The overriding theory as to the main impetus behind ''An Island'' is that it allegorises Blake's rejection of thebluestocking

''Bluestocking'' is a term for an educated, intellectual woman, originally a member of the 18th-century Blue Stockings Society from England led by the hostess and critic Elizabeth Montagu (1718–1800), the "Queen of the Blues", including Eliz ...

society of Harriet Mathew

Harriet Mathew was an 18th-century London socialite and patron of the arts, who is considered an important early patron of John Flaxman and William Blake. She was the wife of the Reverend Anthony Stephen Mathew (also known by the pseudonym Henry ...

, who, along with her husband, Reverend Anthony Stephen Mathew organised 'poetical evenings' to which came many of Blake's friends (such as John Flaxman

John Flaxman (6 July 1755 – 7 December 1826) was a British sculptor and draughtsman, and a leading figure in British and European Neoclassicism. Early in his career, he worked as a modeller for Josiah Wedgwood's pottery. He spent several yea ...

, Thomas Stothard

Thomas Stothard (17 August 1755 – 27 April 1834) was an English painter, illustrator and engraver.

His son, Robert T. Stothard was a painter ( fl. 1810): he painted the proclamation outside York Minster of Queen Victoria's accession to the t ...

and Joseph Johnson Joseph Johnson may refer to:

Entertainment

*Joseph McMillan Johnson (1912–1990), American film art director

*Smokey Johnson (1936–2015), New Orleans jazz musician

* N.O. Joe (Joseph Johnson, born 1975), American musician, producer and songwrit ...

) and, on at least one occasion, Blake himself. The Mathews had been behind the publication in 1783 of Blake's first collection of poetry, ''Poetical Sketches

''Poetical Sketches'' is the first collection of poetry and prose by William Blake, written between 1769 and 1777. Forty copies were printed in 1783 with the help of Blake's friends, the artist John Flaxman and the Reverend Anthony Stephen Mat ...

'', but by 1784, Blake had supposedly grown weary of their company and the social circles in which they moved, and chose to distance himself from them. This theory can be traced back to an 1828 'Biographical Sketch' of Blake by his friend in later life, the painter J. T. Smith, published in the second volume of Smith's biography of Joseph Nollekens

Joseph Nollekens R.A. (11 August 1737 – 23 April 1823) was a sculptor from London generally considered to be the finest British sculptor of the late 18th century.

Life

Nollekens was born on 11 August 1737 at 28 Dean Street, Soho, London, ...

, ''Nollekens and his times''. Smith's references to the Mathew family's association with Blake were taken up and elaborated upon by Blake's first biographer, Alexander Gilchrist

Alexander Gilchrist (182830 November 1861), an English author, is known mainly as a biographer of William Etty and of William Blake. Gilchrist's biography of Blake is still a standard reference work about the poet.

Gilchrist was born at Newingto ...

, in his 1863 biography '' Life of William Blake, Pictor Ignotus.'', and from that point forth, the prevailing belief as to the primary background of ''An Island'' is that it dramatises Blake's disassociation from the social circles in which he found himself.

Critical work in the second half of the twentieth century, however, has often challenged the assumption that ''An Island'' originated in Blake's rejection of a specific social circle. Foremost amongst such work is that of David V. Erdman, who suggests instead that the main background to the ''An Island'' is Blake's belief in his own imminent financial success. In early 1784, Blake opened a print shop at No. 27 Broad Street with James Parker, alongside whom he had served as an apprentice to the engraver James Basire

James Basire (1730–1802

London), also known as James Basire Sr., was a British engraver. He is the most significant of a family of engravers, and noted for his apprenticing of the young William Blake.

Early life

His father was Isaac Basire ...

during the 1770s. At the time, engraving was becoming an extremely lucrative trade, accruing both wealth and respectability for many of its practitioners, and Erdman believes that the increasing prosperity for engravers in the early 1780s represents the most important background to ''An Island'', arguing that the confidence which Blake and Parker must have felt informs the content more so than any sense of social rejection; "the kind of envy that breeds satire is that of the artist and artisan who is anticipating the taste of success and is especially perceptive of the element of opportunism." Erdman also sees as important the fact that the character based on Blake, Quid the Cynic, partially outlines a new method of printing, not unlike Blake's own, as yet unrealised, illuminated printing. Quid argues that he will use this new method of printing to outdo the best known and most successful of artists and writers, such as Joshua Reynolds

Sir Joshua Reynolds (16 July 1723 – 23 February 1792) was an English painter, specialising in portraits. John Russell said he was one of the major European painters of the 18th century. He promoted the "Grand Style" in painting which depend ...

, William Woollett

William Woollett (15 August 173523 May 1785) was an English engraver operating in the 18th century.

Life

Woolett was born in Maidstone, of a family which came originally from the Netherlands.

He was apprenticed to John Tinney, an engraver in F ...

, Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

, John Milton

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet and intellectual. His 1667 epic poem '' Paradise Lost'', written in blank verse and including over ten chapters, was written in a time of immense religious flux and political ...

and William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

. Behind this claim, argues Erdman, "lies the vision of a man ..who begins to see a way to replace the division of labour with the harmony of One Man, to renew and join together the arts of poetry and painting without going outside his own shop and his own head."Erdman (1977: 99) As such, it is Erdman's contention that the primary background factor for ''An Island'' is the sense of anticipation and exuberance on the part of Blake, expectation for his new business venture and excitement regarding his new method of printing; ''An Island'' was thus borne from anticipation.

Nevertheless, writing in 2003, Nick Rawlinson, who also disagrees with the 'rejection theory', points out that "the general critical consensus is that the eleven surviving chapters of this unpublished manuscript form little more than Blake's whimsical attempt to satirise his friends, neighbours and fellow attendees of 27 Rathbone Place

Rathbone Place is a street in central London that runs roughly north-west from Oxford Street to Percy Street. it is joined on its eastern side by Percy Mews, Gresse Street, and Evelyn Yard. The street is mainly occupied by retail and office pre ...

, the intellectual salon of the Reverend and Mrs AS Mathew; a kind of pleasing cartoon wallpaper on which he couldn't resist scrawling a few grotesque caricatures of his favourite scientific and philosophic bugbears."

Manuscript and date

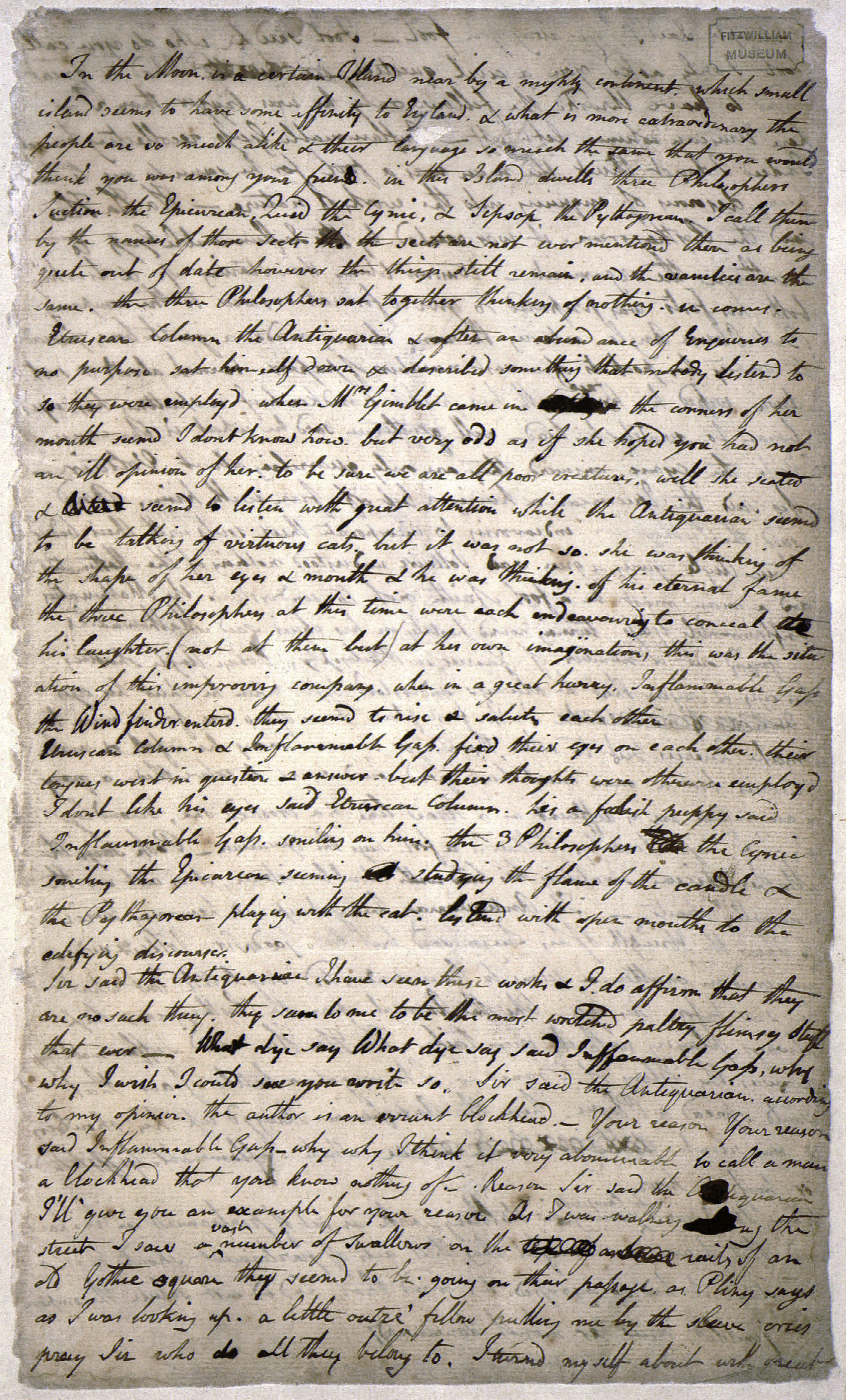

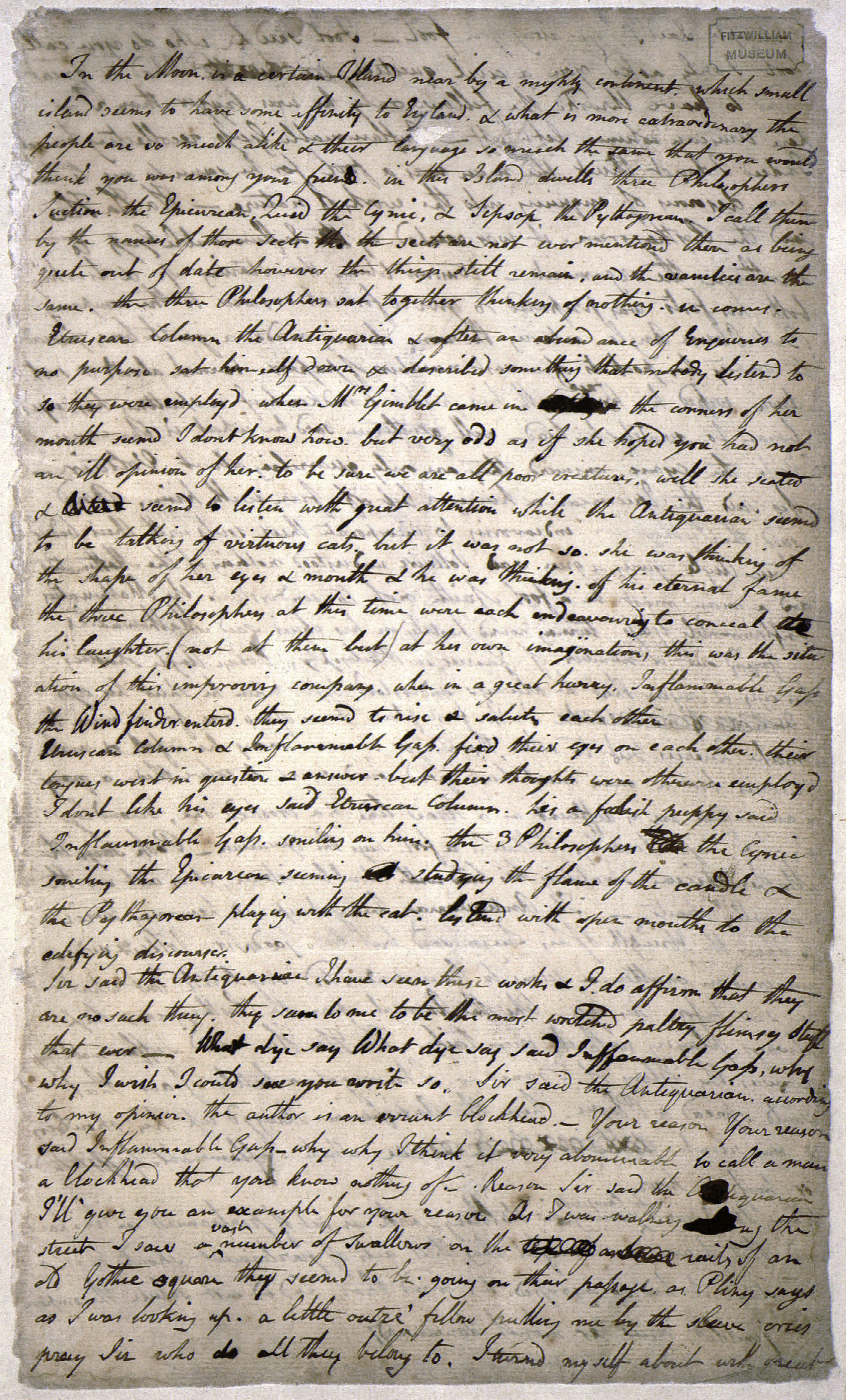

Due to the nature of the revisions in the only existing manuscript copy of ''An Island'', it is generally agreed amongst scholars that the manuscript is not the original, but was in fact a copy made by Blake.Erdman (1982: 849) Blake seems to have worked on the eighteen-page MS over eight sittings, as there are eight different types of ink used throughout.Ackroyd (1995: 89) The manuscript also contains many handwritten corrections in Blake's handwriting. Also of interest is that on the last page of the MS are found numerous small pencil drawings of horses, lambs, lions and two human profiles. Additionally, the word "Numeration" has been written in the centre of the page, the word "Lamb" in tiny script between the two human profiles (partly obscured by a large "N"), and two signatures of Blake himself at the top of the page. Also present are various random letters (especially the letter "N") which may be examples of Blake's attempts to master

Also of interest is that on the last page of the MS are found numerous small pencil drawings of horses, lambs, lions and two human profiles. Additionally, the word "Numeration" has been written in the centre of the page, the word "Lamb" in tiny script between the two human profiles (partly obscured by a large "N"), and two signatures of Blake himself at the top of the page. Also present are various random letters (especially the letter "N") which may be examples of Blake's attempts to master mirror writing

Mirror writing is formed by writing in the direction that is the reverse of the natural way for a given language, such that the result is the mirror image of normal writing: it appears normal when it is reflected in a mirror. It is sometimes u ...

, a skill which was necessary for his work as an engraver. However, it is thought that at least some of the sketches and lettering on this page could have been by Blake's brother, Robert; "the awkwardness and redundancy of some of the work, the bare geometry of the head of the large lion in the lower pair of animals in the upper left quadrant of the page, and the heavy overdrawing on some of the other animals are among the features that may possibly reflect Robert's attempts to draw subjects that had been set as exercises for him by older brother William, and, in some instances, corrected by one of them."

Although the MS contains no date, due to certain topical references, ''An Island'' is generally believed to have been composed in late 1784. For example, there is a reference to the Great Balloon Ascension of September 15, when England's first airship

An airship or dirigible balloon is a type of aerostat or lighter-than-air aircraft that can navigate through the air under its own power. Aerostats gain their lift from a lifting gas that is less dense than the surrounding air.

In early ...

rose from the Artillery Ground

The Artillery Ground in Finsbury is an open space originally set aside for archery and later known also as a cricket venue. Today it is used for military exercises, cricket, rugby and football matches. It belongs to the Honourable Artillery Co ...

in Finsbury

Finsbury is a district of Central London, forming the south-eastern part of the London Borough of Islington. It borders the City of London.

The Manor of Finsbury is first recorded as ''Vinisbir'' (1231) and means "manor of a man called Finn ...

, watched by 220,000 Londoners. Other topical allusions include references to a performing monkey called Mr. Jacko, who appeared at Astley's Amphitheatre

Astley's Amphitheatre was a performance venue in London opened by Philip Astley in 1773, considered the first modern circus ring. It was burned and rebuilt several times, and went through many owners and managers. Despite no trace of the theatr ...

in Lambeth

Lambeth () is a district in South London, England, in the London Borough of Lambeth, historically in the County of Surrey. It is situated south of Charing Cross. The population of the London Borough of Lambeth was 303,086 in 2011. The area expe ...

in July, a performing pig called Toby the Learned Pig, a Handel

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel (; baptised , ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque composer well known for his operas, oratorios, anthems, concerti grossi, and organ concertos. Handel received his training i ...

festival in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

in August, lectures on phlogiston

The phlogiston theory is a superseded scientific theory that postulated the existence of a fire-like element called phlogiston () contained within combustible bodies and released during combustion. The name comes from the Ancient Greek (''burni ...

, exhibitions of the microscope

A microscope () is a laboratory instrument used to examine objects that are too small to be seen by the naked eye. Microscopy is the science of investigating small objects and structures using a microscope. Microscopic means being invisibl ...

, and the Golden Square

Golden Square, in Soho, the City of Westminster, London, is a mainly hardscaped garden square planted with a few mature trees and raised borders in Central London flanked by classical office buildings. Its four approach ways are north and sout ...

parties of Chevalier d'Eon

Chevalier may refer to:

Honours Belgium

* a rank in the Belgian Order of the Crown

* a rank in the Belgian Order of Leopold

* a rank in the Belgian Order of Leopold II

* a title in the Belgian nobility

France

* a rank in the French Legion d'h ...

.

Especially important in dating the text is Miss Gittipin's reference to Miss Filligree; "theres Miss Filligree work she goes out in her coaches & her footman & her maids & Stormonts & Balloon hats & a pair of Gloves every day & the sorrows of Werter & Robinsons & the Queen of Frances Puss colour." Stormonts were a type of hat popular in the early 1780s but falling out of fashion by 1784. Balloon bonnets (linen cases stuffed with hair) had become extremely popular by late 1784, as had Robinson hats and gowns (named after the poet and actress Mary Robinson

Mary Therese Winifred Robinson ( ga, Máire Mhic Róibín; ; born 21 May 1944) is an Irish politician who was the 7th president of Ireland, serving from December 1990 to September 1997, the first woman to hold this office. Prior to her electi ...

). The mention of Werter is also a reference to a hat, not the 1774 novel. The balloon bonnet and the Robinson hat were in vogue from late 1783 to late 1784, when they overlapped slightly with the increasing popularity of the Werter. By mid-1785, however, all three had fallen out of fashion. This serves to situate ''An Island'' in late 1783-late 1784, and taken in tandem with the topical references, seems to confirm a date of the latter half of 1784.

''An Island'' was unpublished during Blake's lifetime, and there is no evidence that it ever got beyond the MS stage. Extracts were first published in ''The Light Blue'', Volume II (1867), a literary magazine published by Cambridge University, however, it has been suggested that perhaps Blake never intended for ''An Island'' to be published at all. Speaking of the sketches and poetry in Blake's Notebook, John Sampson writes they "are in the nature of rough jottings, sometimes mere doggerel set down from whim or to relieve a mood, and never probably ..intended to see the light in cold print. Such without doubt is the fragment known as ''An Island in the Moon''." Peter Ackroyd

Peter Ackroyd (born 5 October 1949) is an English biographer, novelist and critic with a specialist interest in the history and culture of London. For his novels about English history and culture and his biographies of, among others, William ...

agrees with this suggestion, strongly believing that Blake never intended the piece to be read by the public.Ackroyd (1995: 90)

The provenance of the MS is unknown prior to 1893, when it was acquired by Charles Fairfax Murray

Charles Fairfax Murray (30 September 1849 – 25 January 1919) was a British painter, dealer, collector, benefactor, and art historian who was connected with the second wave of the Pre-Raphaelites.

Early years

The youngest of four children, ...

, who gave it to the Fitzwilliam Museum in 1905. At some stage prior to that time, at least one page was removed or lost, as page seventeen does not follow directly from page sixteen. A diagonal pencil inscription at the bottom of page seventeen, not in Blake's hand, reads, "a leaf is evidently missing before one."

Form

The actual form of ''An Island in the Moon'' is difficult to pin down.Geoffrey Keynes

Sir Geoffrey Langdon Keynes ( ; 25 March 1887, Cambridge – 5 July 1982, Cambridge) was a British surgeon and author. He began his career as a physician in World War I, before becoming a doctor at St Bartholomew's Hospital in London, where he ...

classifies it as "an incomplete burlesque novel." Martha W. England compares it to an "afterpiece An afterpiece is a short, usually humorous one-act playlet or musical work following the main attraction, the full-length play, and concluding the theatrical evening.p24 "The Chambers Dictionary"Edinburgh, Chambers,2003 This short comedy, farce, o ...

", one-act satirical plays which were popular in London at the time. Alicia Ostriker

Alicia Suskin Ostriker (born November 11, 1937) is an American poet and scholar who writes Jewish feminist poetry.Powell C.S. (1994) ''Profile: Jeremiah and Alicia Ostriker – A Marriage of Science and Art'', Scientific American 271(3), 28-3 ...

calls it simply a "burlesque

A burlesque is a literary, dramatic or musical work intended to cause laughter by caricaturing the manner or spirit of serious works, or by ludicrous treatment of their subjects.

."Ostriker (1977: 876) Peter Ackroyd refers to it as a "satirical burlesque," and also likens it to an afterpiece. Northrop Frye

Herman Northrop Frye (July 14, 1912 – January 23, 1991) was a Canadian literary critic and literary theorist, considered one of the most influential of the 20th century.

Frye gained international fame with his first book, '' Fearful Symmet ...

, S. Foster Damon and David V. Erdman all refer to it as simply a "prose satire." Frye elaborates upon this definition, calling it "a satire on cultural dilettantism."Frye (1947: 191)

Erdman argues that the piece is a natural progression from Blake's previous work; "out of the sly ironist and angry prophet of ''Poetical Sketches'' emerges the self professed Cynic of ''An Island''." Indeed, Erdman argues that Quid is an evolution of the character of 'William his man' from the unfinished play ''King Edward the Third'', often interpreted as being a self-portrait of Blake himself.

Martha W. England also believes it represents part of Blake’s artistic development and is something of a snapshot of his search for an authentic artistic voice; "we can watch a great metrist and a born parodist searching for his tunes, trying out dramatic systems and metrical systems, none of which were to enslave him. Here he cheerfully takes under his examining eye song and satire, opera

Opera is a form of theatre in which music is a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken by singers. Such a "work" (the literal translation of the Italian word "opera") is typically a collaboration between a composer and a librett ...

and plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pes ...

, surgery and pastoral

A pastoral lifestyle is that of shepherds herding livestock around open areas of land according to seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. It lends its name to a genre of literature, art, and music (pastorale) that depicts ...

, Chatterton and science, enthusiasm and myth, philanthropy and Handelian anthem, the Man in the Street and those children whose nursery is the street – while he is making up his mind what William Blake shall take seriously ..here, a master ironist flexes his vocal cords with a wide range of tone."

Similarly, Robert N. Essick, Joseph Viscomi and Morris Eaves see it as foreshadowing much of Blake's later work; "''An Island in the Moon'' underscores the importance of the extensive stretches of humour and satire that show up frequently among his other writings. So, although Blake left it orphaned, untitled, and unfinished in a heavily revised manuscript, ''Island'' is in some sense a primary literary experiment for him, setting the undertone of much to follow."

''An Island'' has no coherent, overall structure, no plot whatsoever, being instead a broad satire. According to Ackroyd, "it is not a generalised satire on a Swiftian model; it stays too close to lake'sown world for that." As such, it is primarily composed of snatches of trivial conversation and witticisms, interspersed with songs and ballads. In this sense, it is structured similarly to Samuel Foote

Samuel Foote (January 1720 – 21 October 1777) was a British dramatist, actor and theatre manager. He was known for his comedic acting and writing, and for turning the loss of a leg in a riding accident in 1766 to comedic opportunity.

Early l ...

's improvised series of dramas '' Tea at the Haymarket'', which lacked a definitive form so as to get around licensing regulations. England believes that Blake was consciously borrowing from Foote's style in composing ''An Island'' and as such, it is an "anti-play."

Nick Rawlinson agrees with England's assessment, although he feels that Samuel Foote may have been more of an influence than England allows for. Rawlinson reads the piece as primarily about reading itself, and the social implications of certain types of reading; "inside the apparently random concoction of prose, song and slapstick

Slapstick is a style of humor involving exaggerated physical activity that exceeds the boundaries of normal physical comedy. Slapstick may involve both intentional violence and violence by mishap, often resulting from inept use of props such a ...

..lies an extraordinary, almost dazzling examination of the relationship between our habits of reading and the society they produce ..Blake consistently and consciously foregrounds how our understanding of our society, our voices and even our perceptions are governed by our habits of reading ..''An Island'' contains a deliberate and careful plan to challenge ocialmisreadings by teaching us how to read the world comically. It is nothing less than a degree course in comic Vision." Rawlinson argues that the literary references in the text are structured to mirror a 1707 Cambridge University pamphlet entitled ''A Method of Instructing Pupils'' (a guide on how to teach Philosophy). As such Rawlinson feels ''An Island'' is best described as "philosoparody."

Characters

Many of the characters in ''An Island'' areparodies

A parody, also known as a spoof, a satire, a send-up, a take-off, a lampoon, a play on (something), or a caricature, is a creative work designed to imitate, comment on, and/or mock its subject by means of satiric or ironic imitation. Often its sub ...

of Blake's friends and acquaintances, although there is considerable critical disagreement as to whom some characters represent. Indeed, some scholars question the usefulness of trying to discover whom ''any'' of them represent. Northrop Frye, for example, argues "the characters are not so much individuals as representatives of the various types of "reasoning" which are satirised." Peter Ackroyd also suggests that understanding whom the characters represent is less important than understanding the satire at the heart of the piece. Similarly, Nick Rawlinson argues that trying to attach the characters to specific people "limits the scope of the work to the eighteenth-century equivalent of a scurrilous email ..it is reasonable to assume that the various characters stand for something more than just amusing personality sketches ..It may be more helpful to see the characters as a reflection not just of a real person but also of an attitude Blake wishes to question."

Nevertheless, much critical work has been done on endeavouring to unravel which real life person is behind each of the fictional characters.

* Quid the Cynic – based on Blake;Damon (1988: 199) represents cynicism and doubt; S. Foster Damon calls him "a lusty caricature of Blake himself ..a poet who characteristically runs down those he admires most." Rawlinson suggests his name may be derived from the word 'Quidnunc'; a popular term in the eighteenth century for a busybody and know-it-all.

* Suction the Epicurean – based on Blake's brother, Robert; hates mathematics and science, and lives instead by his feelings. Damon believes he represents "the philosophy of the senses"Damon (1988: 200) and is "an all-absorbing atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

."Damon (1988: 374) Rawlinson suggests he may be a composite of Robert Blake and the print seller Jemmy Whittle.Rawlinson (2003: 107) Suction is an Epicurean

Epicureanism is a system of philosophy founded around 307 BC based upon the teachings of the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus. Epicureanism was originally a challenge to Platonism. Later its main opponent became Stoicism.

Few writings by Epi ...

, a philosophical school despised by Blake, because of its rejection of the importance of the spirit, and reliance on materialism

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism which holds matter to be the fundamental substance in nature, and all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical materiali ...

, which he associated with Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

. Circa 1808, Blake would write, "Bacon is only Epicurus over again."

* Sipsop the Pythagorean – Geoffrey Keynes suggests that Sipsop is based on the neoplatonist

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some ide ...

Thomas Taylor with whose work Blake was familiar. Keynes is supported in this by Alicia Ostriker. However, David V. Erdman, disputes this theory and instead suggests that Sipsop is based on William Henry Mathew, eldest son of Anthony Stephen Mathew. Erdman bases this argument on the fact that William Henry was apprenticed to the surgeon John Hunter, who is represented in ''An Island'' by Jack Tearguts, to whom Sipsop is apprenticed. On the other hand, Nancy Bogen believes that Sipsop is based on John Abernethy John Abernethy may refer to:

* John Abernethy (bishop), Scottish bishop, died 1639

* John Abernethy (judge) (born 1947), Australian judge

*John Abernethy (minister) (1680–1740), Presbyterian minister in Ireland

*John Abernethy (surgeon) (1764–18 ...

. Sipsop is often posited as representing the science rejected by Suction, but Damon argues this cannot be so, as such science is represented by Inflammable Gass. To Damon's mind, this leaves Sipsop with something of an undefined role. As a Pythagorean

Pythagorean, meaning of or pertaining to the ancient Ionian mathematician, philosopher, and music theorist Pythagoras, may refer to:

Philosophy

* Pythagoreanism, the esoteric and metaphysical beliefs purported to have been held by Pythagoras

* Ne ...

, Sipsop is ideologically the opposite of Suction the Epicurean; Pythagoreanism embraces the mysticism that Epicureanism explicitly rejects. Robert Schofield identifies this figure as Erasmus Darwin

Erasmus Robert Darwin (12 December 173118 April 1802) was an English physician. One of the key thinkers of the Midlands Enlightenment, he was also a natural philosopher, physiologist, slave-trade abolitionist, inventor, and poet.

His poems ...

. Darwin was one of the chief members of the Lunar Society

The Lunar Society of Birmingham was a British dinner club and informal learned society of prominent figures in the Midlands Enlightenment, including industrialists, natural philosophers and intellectuals, who met regularly between 1765 and 1813 ...

, an informal 18thC club of scientific philosophers, that held meetings on the night of the full moon. Blake had met Darwin and Priestly (another Lunar Society member) at Joseph Johnson Joseph Johnson may refer to:

Entertainment

*Joseph McMillan Johnson (1912–1990), American film art director

*Smokey Johnson (1936–2015), New Orleans jazz musician

* N.O. Joe (Joseph Johnson, born 1975), American musician, producer and songwrit ...

's home and had engraved an illustration in Darwin's ''The Botanic Garden

''The Botanic Garden'' (1791) is a set of two poems, ''The Economy of Vegetation'' and ''The Loves of the Plants'', by the British poet and naturalist Erasmus Darwin. ''The Economy of Vegetation'' celebrates technological innovation and scien ...

,'' a lengthy scientific poem that used mythological images to explain scientific discoveries.

* Steelyard the Lawgiver – based on Blake's close friend and fellow artist John Flaxman.

* Inflammable Gass – Damon suggests he may be based on the scientist and philosopher Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted exp ...

, as Gass' reference to "flogiston" recalls Priestley's experiments with phlogiston

The phlogiston theory is a superseded scientific theory that postulated the existence of a fire-like element called phlogiston () contained within combustible bodies and released during combustion. The name comes from the Ancient Greek (''burni ...

, which were quite well known at the time. G.E. Bentley reaches a similar conclusion, citing a demonstration given at the Free Masons Tavern on Great Queen Street

Great Queen Street is a street in the West End of central London in England. It is a continuation of Long Acre from Drury Lane to Kingsway. It runs from 1 to 44 along the north side, east to west, and 45 to about 80 along the south side, w ...

during which some phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element with the symbol P and atomic number 15. Elemental phosphorus exists in two major forms, white phosphorus and red phosphorus, but because it is highly reactive, phosphorus is never found as a free element on Ear ...

ignited and destroyed the lamp containing it. Bentley believes that this incident may have formed the basis for the broken glass during an experiment in chapter 10. Erdman however, rejects this identification, arguing that there is no evidence Blake was familiar with either the demonstrations or the writings of Priestley. Instead, Erdman suggests that Gass may simply be a characteristic type representing all science in general. In 1951, Palmer Brown suggested that Gass may be based on the conjurer Gustavus Katterfelto, who was as famous as Priestley in London, and who carried out public experiments in Piccadilly

Piccadilly () is a road in the City of Westminster, London, to the south of Mayfair, between Hyde Park Corner in the west and Piccadilly Circus in the east. It is part of the A4 road that connects central London to Hammersmith, Earl's Court, ...

. Although Erdman initially rejected Brown's theory, he changed his mind shortly before writing '' Blake: Prophet Against Empire'', and ultimately came to support it. Another possibility, suggested by W.H. Stevenson, is William Nicholson, author of ''An Introduction to Natural Philosophy'', for which Blake engraved the title page vignette in 1781. Other possibilities, suggested by Stanley Gardner, are the physician George Fordyce

George Fordyce (18 November 1736 – 25 May 1802) was a distinguished Scotland, Scottish physician, lecturer on medicine, and chemist, who was a Fellow of the Royal Society and a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians.

Early life

George Fo ...

and the scientist Henry Cavendish

Henry Cavendish ( ; 10 October 1731 – 24 February 1810) was an English natural philosopher and scientist who was an important experimental and theoretical chemist and physicist. He is noted for his discovery of hydrogen, which he termed "infl ...

. Rawlinson suggests Gass could, at least in part, be based on the botanist Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the 1766 natural-history expedition to Newfoundland and Labrador. He took part in Captain James ...

.

* Obtuse Angle – generally agreed to be based on James Parker, Blake’s fellow apprentice during his time with Basire. George Mills Harper, however, believes that Angle is instead based on Thomas Taylor (Harper agrees with Erdman that Sipsop is not based on Taylor but on William Henry Mathew). Harper argues that Angle seems to be an educator, and his relationship with many of the other characters is that of a teacher and student. This is significant because there is evidence that Blake took lessons in Euclid

Euclid (; grc-gre, Wikt:Εὐκλείδης, Εὐκλείδης; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the ''Euclid's Elements, Elements'' trea ...

under Taylor, hence Angle's apparent role as teacher. Erdman supports this theory. Rawlinson suggests that Angle may be partially based on Blake's friend George Cumberland

George Cumberland (27 November 1754 – 8 August 1848) was an English art collector, writer and poet. He was a lifelong friend and supporter of William Blake, and like him was an experimental printmaker. He was also an amateur watercolouris ...

, as well as the antiquarian Francis Douce

Francis Douce ( ; 175730 March 1834) was a British antiquary and museum curator.

Biography

Douce was born in London. His father was a clerk in Chancery. After completing his education he entered his father's office, but soon quit it to devote ...

.

* Aradobo – based on either Joseph Johnson, the first publisher to employ Blake as a copy-engraver,Erdman (1977: 96) or one of the book seller Edward brothers (James, John and Richard). In 1784, James and John had opened a book shop in Pall Mall, with Richard as their apprentice, and Blake would certainly have been familiar with the shop.

* Etruscan Column – Harper believes that Column is based on the antiquarian John Brand. However, Brylowe points out that the Greek antiquarianism Blake is mocking is more in line with the work of William Hamilton.

* Little Scopprell – Erdman suggests he may represent J. T. Smith, but he acknowledges that this is based on guesswork only.Erdman (1977: 98n17)

* Tilly Lally – no known basis for this character, although he is often posited as representing elegance.

* Mrs. Nannicantipot – based on the poet and children's author Anna Laetitia Barbauld

Anna Laetitia Barbauld (, by herself possibly , as in French, Aikin; 20 June 1743 – 9 March 1825) was a prominent English poet, essayist, literary critic, editor, and author of children's literature. A " woman of letters" who published in mu ...

.

* Gibble Gabble – because she is married to Gass, she is usually seen as representing Joseph Priestley's real wife, Mary Priestley. However, there is some disagreement about whether Gass actually represents Priestley, and if not, then presumably, Gibble Gabble could no longer be posited as representing Mary.

* Mrs Gimblet – possibly based on Harriet Mathew. Rawlinson suggests she could be based on Charlotte Lennox

Charlotte Lennox, ''née'' Ramsay (c. 1729 – 4 January 1804), was a Scottish novelist, playwright, poet, translator, essayist, and magazine editor, who has primarily been remembered as the author of ''The Female Quixote'', and for her associ ...

.

* Mrs Gittipin – possibly based on Nancy Flaxman, John Flaxman's wife.

* Ms. Sigtagatist – Nancy Bogen suggests she is based on Harriet Mathew, but Erdman believes this is doubtful. The name "Sigtagatist" was first written "Sistagatist" in most places, but changed. Twice during the piece, she is sarcastically referred to as Mrs Sinagain; once by Tily Lally in Chapter 3d ("Ill tell you what Mrs Sinagain I dont think theres any harm in it"), and once by the narrator in Chapter 4 ("Ah," said Mrs Sinagain. "I'm sure you ought to hold your tongue, for you never say any thing about the scriptures, & you hinder your husband from going to church").

* Jack Tearguts – mentioned only; based on the surgeon and lecturer John Hunter, whose name Blake wrote in the manuscript before replacing it with Jack Tearguts.

* Mr. Jacko – mentioned only; possibly based on portrait painter Richard Cosway

Richard Cosway (5 November 1742 – 4 July 1821) was a leading English portrait painter of the Georgian and Regency era, noted for his miniatures. He was a contemporary of John Smart, George Engleheart, William Wood, and Richard Crosse. ...

; probably named after a famous performing monkey well known in London at the time.

* Mrs. Nann – mentioned only; Nancy Bogen believes she is based on Blake's wife, Catherine

Katherine, also spelled Catherine, and other variations are feminine names. They are popular in Christian countries because of their derivation from the name of one of the first Christian saints, Catherine of Alexandria.

In the early Christ ...

, but Erdman believes this is guesswork.

Overview

Chapter 1 begins with a promise by the narrator to engage the reader with an analysis of contemporary thought, "but the grand scheme degenerates immediately into nonsensical and ignorant chatter." A major theme in this chapter is that no one listens to anyone else; "Etruscan Column & Inflammable Gass fix'd their eyes on each other, their tongue went in question & answer, but their thoughts were otherwise employed." According to Erdman, "the contrast between appearance and reality in the realm of communication lies at the centre of Blake's satiric method." This chapter also introduces Blake's satiric treatment of the sciences and mathematics; according to Obtuse Angle, "

Chapter 1 begins with a promise by the narrator to engage the reader with an analysis of contemporary thought, "but the grand scheme degenerates immediately into nonsensical and ignorant chatter." A major theme in this chapter is that no one listens to anyone else; "Etruscan Column & Inflammable Gass fix'd their eyes on each other, their tongue went in question & answer, but their thoughts were otherwise employed." According to Erdman, "the contrast between appearance and reality in the realm of communication lies at the centre of Blake's satiric method." This chapter also introduces Blake's satiric treatment of the sciences and mathematics; according to Obtuse Angle, "Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his ...

understood nothing of the Mathematics, and a man must be a fool ifaith not to understand the Mathematics."

Chapter 2d is the shortest chapter in the piece and is only one sentence long. The entire chapter reads: "Tilly Lally the Siptippidist Aradobo, the dean of Morocco, Miss Gittipin & Mrs Nannicantipot, Mrs Sigtagatist Gibble Gabble the wife of Inflammable Gass – & Little Scopprell enter'd the room (If I have not presented you with every character in the piece call me *Arse—)"

Chapter 3d introduces musical interludes, a technique which becomes increasingly important as the piece moves on. "Honour & Genius", sung by Quid, is a parody of a song in the James Harris pastoral ''The Spring

''The Spring'' (or ''La Source'') is a large oil painting created in 1912 by the French artist Francis Picabia. The work, both Cubist and abstract, was exhibited in Paris at the Salon d'Automne of 1912. The Cubist contribution to the 1912 Salo ...

'' (1762 – reissued in 1766 as ''Daphnis and Amaryllis''). The satirical vein continues in this chapter during the discussion of " Phebus", when Obtuse Angle claims "he was the God of Physic

Physic may refer to:

* The study or practice of medicine

* A substance administered as medicine, or the medicinal plant from which it is extracted:

** '' Gillenia stipulata'', a plant known commonly as Indian physic

** ''Jatropha'', a genus of pla ...

, Painting

Painting is the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called the "matrix" or "support"). The medium is commonly applied to the base with a brush, but other implements, such as knives, sponges, and ...

, Perspective, Geometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is c ...

, Geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and ...

, Astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

, Cookery

Cooking, cookery, or culinary arts is the art, science and craft of using heat to prepare food for consumption. Cooking techniques and ingredients vary widely, from grilling food over an open fire to using electric stoves, to baking in vario ...

, Chymistry, Conjunctives, Mechanics

Mechanics (from Ancient Greek: μηχανική, ''mēkhanikḗ'', "of machines") is the area of mathematics and physics concerned with the relationships between force, matter, and motion among physical objects. Forces applied to objects r ...

, Tactics

Tactic(s) or Tactical may refer to:

* Tactic (method), a conceptual action implemented as one or more specific tasks

** Military tactics, the disposition and maneuver of units on a particular sea or battlefield

** Chess tactics

** Political tact ...

, Pathology

Pathology is the study of the causes and effects of disease or injury. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in ...

, Phraseology

In linguistics, phraseology is the study of set or fixed expressions, such as idioms, phrasal verbs, and other types of multi-word lexical units (often collectively referred to as ''phrasemes''), in which the component parts of the expression tak ...

, Theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

, Mythology

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not objectively true, the identification of a narrat ...

, Astrology

Astrology is a range of Divination, divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of Celestial o ...

, Osteology

Osteology () is the scientific study of bones, practised by osteologists. A subdiscipline of anatomy, anthropology, and paleontology, osteology is the detailed study of the structure of bones, skeletal elements, teeth, microbone morphology, funct ...

, Somatology

Biological anthropology, also known as physical anthropology, is a scientific discipline concerned with the biological and behavioral aspects of human beings, their extinct hominin ancestors, and related non-human primates, particularly from an e ...

, in short every art & science adorn'd him as beads round his neck."

Chapter 4 continues with the satire in the form of a debate between Inflammable Gass and Mrs. Sigtagatist. When Sigtagatist tells Gass that he should always attend church on Sundays, Gass declares, "if I had not a place of profit that forces me to go to church I'd see the parsons all hang'd a parcel of lying." Sigtigatist then proclaims "O, if it were not for churches & chapels I should not have liv'd so long." She then proudly recalls a figure from her youth, Minister Huffcap, who would "kick the bottom of the Pulpit out, with Passion, would tear off the sleeve of his Gown, & set his wig on fire & throw it at the people he'd cry & stamp & kick & sweat and all for the good of their souls."

Chapter 5 looks at the inanity of the society depicted, insofar as an intellectual discussion of the work of Chatterton between Obtuse Angle, Little Scopprell, Aradobo and Tilly Lally descends into farce; "Obtuse Angle said in the first place you thought he was not Mathematician& then afterwards when I said he was not you thought he was not. Why I know that – Oh no sir I thought that he was not, but I ask'd to know whether he was. – How can that be said Obtuse Angle how could you ask & think that he was not – why said he. It came into my head that he was not. – Why then said Obtuse Angle you said that he was. Did I say so Law I did not think I said that – Did not he said Obtuse Angle Yes said Scopprell. But I meant said Aradobo I I I can't think Law Sir I wish you'd tell me, how it is." Northrop Frye refers to this incident as "farcical conversational deadlock."

Chapter 6 continues to intersperse songs amongst the prose. "When old corruption", sung by Quid, is a satire on the medical profession and may have been suggested by '' The Devil Upon Two Sticks'' (1768), a three-act comedic satire by Samuel Foote

Samuel Foote (January 1720 – 21 October 1777) was a British dramatist, actor and theatre manager. He was known for his comedic acting and writing, and for turning the loss of a leg in a riding accident in 1766 to comedic opportunity.

Early l ...

, which was itself based on the satirical Alain-René Lesage

Alain-René Lesage (; 6 May 166817 November 1747; older spelling Le Sage) was a French novelist and playwright. Lesage is best known for his comic novel '' The Devil upon Two Sticks'' (1707, ''Le Diable boiteux''), his comedy ''Turcaret'' (170 ...

novel ''Le Diable boiteux'' (1707). ''The Devil Upon Two Sticks'' had been revived on the London stage in 1784, so it would have been topical at the time of writing. The poem also seems to parody parts of Book II of the John Milton epic ''Paradise Lost

''Paradise Lost'' is an epic poem in blank verse by the 17th-century English poet John Milton (1608–1674). The first version, published in 1667, consists of ten books with over ten thousand lines of verse (poetry), verse. A second edition fo ...

'' (1667), particularly the scenes outlining the genealogy of the sentries of the Gates of Hell, Sin

In a religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considered immoral, selfish, s ...

and Death

Death is the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain an organism. For organisms with a brain, death can also be defined as the irreversible cessation of functioning of the whole brain, including brainstem, and brain ...

. Chapter 6 is also an important chapter for Suction, insofar as it is here he outlines his primary philosophy; "Ah hang your reasoning I hate reasoning I do every thing by my feelings." The satire in this section comes from Sipsop's discussion of the surgery of Jack Tearguts, and how his patients react; "Tho they cry ever so he'll Swear at them & keep them down with his fist & tell them that he'll scrape their bones if they don't lie still & be quiet." The inherent but unacknowledged irony here recalls Sigtagatist's proud recollection of Minister Huffcap in Chapter 4.

Chapter 7 sees Suction continue to espouse his philosophical beliefs; "Hang philosophy – I would not give a farthing for it do all by your feelings and never think at all about it." Similarly, Quid voices his own opinion of some of the most respected writers at the time; "I think that Homer is bombast & Shakespeare is too wild & Milton has no feelings they might be easily outdone Chatterton never writ those poems." In relation to this criticism, Damon comments, "he is merely repeating the conventional chatter of the critics, which was the exact opposite of what Blake actually thought."

Chapter 8 contains references to and quotes from many of the works Blake was exposed to and influenced by at a young age. These references include allusions to Saint Jerome

Jerome (; la, Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was a Christian priest, confessor, theologian, and historian; he is comm ...

, John Taylor's '' Urania, or his Heavenly Muse'' (1630), Abraham Cowley

Abraham Cowley (; 161828 July 1667) was an English poet and essayist born in the City of London late in 1618. He was one of the leading English poets of the 17th century, with 14 printings of his ''Works'' published between 1668 and 1721.

Early ...

's translation of Anacreon

Anacreon (; grc-gre, Ἀνακρέων ὁ Τήϊος; BC) was a Greek lyric poet, notable for his drinking songs and erotic poems. Later Greeks included him in the canonical list of Nine Lyric Poets. Anacreon wrote all of his poetry in the ...

's lyric poem "The Grasshopper" (1656), Henry Wotton

Sir Henry Wotton (; 30 March 1568 – December 1639) was an English author, diplomat and politician who sat in the House of Commons in 1614 and 1625. When on a mission to Augsburg, in 1604, he famously said, "An ambassador is an honest gentlema ...

's '' Reliquae Wottonianae'' (1685), John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism ...

's ''An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

''An Essay Concerning Human Understanding'' is a work by John Locke concerning the foundation of human knowledge and understanding. It first appeared in 1689 (although dated 1690) with the printed title ''An Essay Concerning Humane Understand ...

'' (1690), Joseph Addison

Joseph Addison (1 May 1672 – 17 June 1719) was an English essayist, poet, playwright and politician. He was the eldest son of The Reverend Lancelot Addison. His name is usually remembered alongside that of his long-standing friend Richard S ...

's ''Cato, a Tragedy

''Cato, a Tragedy'' is a play written by Joseph Addison in 1712 and first performed on 14 April 1713. It is based on the events of the last days of Marcus Porcius Cato Uticensis (better known as Cato the Younger) (95–46 BC), a Stoic whose deeds ...

'' (1712), Edward Young

Edward Young (c. 3 July 1683 – 5 April 1765) was an English poet, best remembered for ''Night-Thoughts'', a series of philosophical writings in blank verse, reflecting his state of mind following several bereavements. It was one of the mos ...

's ''Night-Thoughts

''The Complaint: or, Night-Thoughts on Life, Death, & Immortality'', better known simply as ''Night-Thoughts'', is a long poem by Edward Young published in nine parts (or "nights") between 1742 and 1745. It was illustrated with notable engrav ...

'' (1742) and James Hervey

James Hervey (26 February 1714 – 25 December 1758) was an English clergyman and writer.

Life

He was born at Hardingstone, near Northampton, and was educated at the grammar school of Northampton, and at Lincoln College, Oxford. Here he came ...

's '' Meditations and Contemplations'' (1746) and '' Theron and Aspasio'' (1755). The Jerome reference is found in Steelyard's comment "Says Jerome happiness is not for us poor crawling reptiles of the earth Talk of happiness & happiness its no such thing – every person has a something." The Taylor reference is Steelyard’s poem; "Hear then the pride & knowledge of a Sailor/His sprit sail fore sail main sail & his mizen/A poor frail man god wot I know none frailer/I know no greater sinner than John Taylor." Although Alicia Ostriker feels this is a reference to the preacher John Taylor,Ostriker (1977: 877) David Erdman argues that the lines closely parallel the opening of the poem ''Urania '', and as such, the reference is more likely to the poet than the preacher. The Cowley reference is found in the poem "Phebe drest like beauties Queen", which contains the lines "Happy people who can be/In happiness compard with ye." Erdman believes this to be derived from the lines in Cowley's translation of Anacreon, "Happy Insect! What can be/In Happiness compar'd to thee?" The Wotton reference is found in Steelyard's "My crop of corn is but a field of tares;" John Sampson believes this to be reference to the Chidiock Tichborne

Chidiock Tichborne (after 24 August 1562 – 20 September 1586), erroneously referred to as Charles, was an English conspirator and poet.

Life

Tichborne was born in Southampton sometime after 24 August 1562Phillimore, Hampshire Parish Records, ...

poem "Elegy" (1586), which Blake could have been familiar with from Wotton's ''Reliquae''. Locke is mentioned when Scopprell picks up one of Steelyard's books and reads the cover, "An Easy of Huming Understanding by John Lookye Gent." Addison is referred to indirectly when Steelyard attributes the quote "the wreck of matter & the crush of worlds" to Edward Young, when it is actually from Addison's ''Cato''. Both the reference to Young and Hervey's ''Meditations'' are found in the opening sentence of the chapter; "Steelyard the Lawgiver, sitting at his table taking extracts from Herveys Meditations among the tombs & Youngs Night thoughts." The ''Theron'' reference is found when Steelyard announces to Obtuse Angle that he is reading the book.

Chapter 9 includes a number of songs that seemingly have no real meaning, but which would rhythmically appeal to infants. For example, "This frog he would a wooing ride/Kitty alone Kitty alone/This frog he would a wooing ride/Kitty alone & I" was a real ditty popular in London at the time. Such songs possibly reflect Blake's childhood. Other songs in this chapter include "Lo the Bat with Leathern wing", which may be a combined parody of a line in Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, ...

's ''An Essay on Man

''An Essay on Man'' is a poem published by Alexander Pope in 1733–1734. It was dedicated to Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke, (pronounced 'Bull-en-brook') hence the opening line: "Awake, St John...". It is an effort to rationalize or r ...

'' (1734); "Lo, the poor Indian", and a phrase in William Collins' "Ode to Evening

An ode (from grc, ᾠδή, ōdḗ) is a type of lyric poetry. Odes are elaborately structured poems praising or glorifying an event or individual, describing nature intellectually as well as emotionally. A classic ode is structured in three majo ...

"; "weak eyed bat/With short shrill shriek flits by on leathern wing." Satire is found in this chapter in the songs "Hail Matrimony made of Love", which condemns marriage, and may have been inspired by ''The Wife Hater'' by John Cleveland

John Cleveland (16 June 1613 – 29 April 1658) was an English poet who supported the Royalist cause in the English Civil War. He was best known for political satire.

Early life

Cleveland was born in Loughborough, the son of Thomas Cleveland, ...

(1669). Satire is also present in "This city & this country", which mocks patriotism, and could be a parody of a patriotic ballad entitled "The Roast Beef of Old England" from Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding (22 April 1707 – 8 October 1754) was an English novelist, irony writer, and dramatist known for earthy humour and satire. His comic novel '' Tom Jones'' is still widely appreciated. He and Samuel Richardson are seen as founders ...

's play ''The Grub Street Opera

''The Grub Street Opera'' is a play by Henry Fielding that originated as an expanded version of his play ''The Welsh Opera''. It was never put on for an audience and is Fielding's single print-only play. As in ''The Welsh Opera'', the author of t ...

'' (1731). This chapter also contains references to Thomas Sutton

Thomas Sutton (1532 – 12 December 1611) was an English civil servant and businessman, born in Knaith, Lincolnshire. He is remembered as the founder of the London Charterhouse and of Charterhouse School.

Life

Sutton was the son of an official ...

, founder of the Charterhouse School

(God having given, I gave)

, established =

, closed =

, type = Public school Independent day and boarding school

, religion = Church of England

, president ...

in 1611, the churchman Robert South

Robert South (4 September 1634 – 8 July 1716) was an English churchman who was known for his combative preaching and his Latin poetry.

Early life

He was the son of Robert South, a London merchant, and Elizabeth Berry. He was born at Hackney, ...

and William Sherlock

William Sherlock (c. 1639/1641June 19, 1707) was an English church leader.

Life

He was born at Southwark, the son of a tradesman, and was educated at St Saviour's Grammar School and Eton, and then at Peterhouse, Cambridge. In 1669 he became r ...

's '' A Practical Discourse upon Death'' (1689).

Chapter 10 concludes with Inflammable Gass accidentally releasing a "Pestilence", which he fears will kill everyone on the Island; "While Tilly Lally & Scopprell were pumping at the air pump Smack went the glass. Hang said Tilly Lally. Inflammable Gass turn'd short round & threw down the table & Glasses & Pictures & broke the bottles of wind, & let out the Pestilence. He saw the Pestilence fly out of the bottle & cried out while he ran out of the room. Go come out come out you are we are putrified, we are corrupted. our lungs are destroy'd with the Flogiston this will spread a plague all thro' the Island he was down stairs the very first on the back of him came all the others in a heap so they need not bidding go." However, no mention is made of the incident in the next chapter; a possible allusion to Blake's distrust of science.

Chapter 11 is seen as the most important chapter by many critics insofar as it contains early versions of "The Little Boy lost

"The Little Boy Lost" is a simple lyric poem written by William Blake. This poem is part of a larger work entitled ''Songs of Innocence'' which was published in the year 1789. "The Little Boy Lost" is a prelude to "The Little Boy Found".

Summa ...

", "Holy Thursday

Maundy Thursday or Holy Thursday (also known as Great and Holy Thursday, Holy and Great Thursday, Covenant Thursday, Sheer Thursday, and Thursday of Mysteries, among other names) is the day during Holy Week that commemorates the Washing of the ...

", and "Nurse's Song

''Nurse's Song'' is the name of two related poems by William Blake, published in ''Songs of Innocence'' in 1789 and ''Songs of Experience

''Songs of Innocence and of Experience'' is a collection of illustrated poems by William Blake. It appe ...

", all of which would appear in ''Songs of Innocence'' in 1789. This chapter also includes an incomplete description of Blake's method of illuminated printing. The description begins in the middle, with at least one preceding page missing, as Quid explains his method to Mrs. Gittipin; "... them Illuminating the Manuscript-Ay said she that would be excellent. Then said he I would have all the writing Engraved instead of Printed & at every other leaf a high finish'd print all in three Volumes folio, & sell them a hundred pounds a piece. They would Print off two thousand then said she whoever will not have them will be ignorant fools & will not deserve to live." Damon has speculated that Blake may have destroyed the missing page(s) so as to preserve the secret of his method.

Adaptations

''An Island in the Moon'' has been adapted for the stage twice. In 1971, Roger Savage adapted it into a two-act play entitled ''Conversations with Mr. Quid'', which was staged at theUniversity of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

as part of a week-long Blake conference.Phillips (1987: 23n35)

The second adaptation was in 1983, when Blake scholar Joseph Viscomi adapted it into a one-act musical under the title ''An Island in the Moon: A Satire by William Blake, 1784''. The piece was staged in the Goldwin Smith Hall on Cornell University

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to teach an ...

's Central Campus as part of the Cornell Blake Symposium, ''Blake: Ancient and Modern''. Viscomi wrote the adaptation himself, which included musical versions of " The Garden of Love" from ''Songs of Innocence and of Experience'' (1794) and "O why was I born with a different face", a poem from a letter written by Blake to Thomas Butts in 1803. Original music was composed by Margaret LaFrance. Department of Theatre lecturers Evamarii Johnson and Robert Gross directed and produced, respectively. Viscomi consolidated all of the events of the piece into a single night in a tavern (owned by Tilly Lally, who also doubled as the narrator), and reduced the cast from fifteen to fourteen by removing Mrs Nannicantipot. Viscomi also moved the last section to earlier in the play, and thus the play ends with the various songs from Chapter 11 which would appear in ''Songs of Innocence''.

References

Citations

Further reading

*Ackroyd, Peter

Peter Ackroyd (born 5 October 1949) is an English biographer, novelist and critic with a specialist interest in the history and culture of London. For his novels about English history and culture and his biographies of, among others, William ...

. ''Blake'' (London: Vintage, 1995)

* Bentley, G. E. Jr and Nurmi, Martin K. ''A Blake Bibliography: Annotated Lists of Works, Studies and Blakeana'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1964)

* Bentley, G. E. Jr (ed.) ''William Blake: The Critical Heritage'' (London: Routledge, 1975)

* . ''Blake Books: Annotated Catalogues of William Blake's Writings'' (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977)

* . ''William Blake's Writings'' (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978)

* . ''The Stranger from Paradise: A Biography of William Blake'' (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001)

* Brylowe, Thora. "Of Gothic Architects and Grecian Rods: William Blake, Antiquarianism and the History of Art" Romanticism. Volume 18, pages 89–104 DOI 10.3366/rom.2012.0066, , Available Online April 2012 .

* Bogen, Nancy. "William Blake's ''Island in the Moon'' Revisited", ''Satire Newsletter'', V (1968), 110–117

* Campbell, William Royce. "The Aesthetic Integrity of Blake's ''Island in the Moon''", ''Blake Studies'', 3:1 (Spring, 1971), 137–147

* Castanedo, Fernando. "‘Mr. Jacko:’ Prince-Riding in Blake’s ''An Island in the Moon''", ''Notes and Queries'', 64:1 (2017), 27-29.

* . "On Blinks and Kisses, Monkeys and Bears: Dating William Blake’s ''An Island in the Moon''", ''Huntington Library Quarterly'', 80:3 (2017), 437-452.

* . "Blake: Milton Had ‘Odd Feelings’ -- Rather than None", ''Notes and Queries'', 64:4 (2017), 549-550.

* . "A Blake Riddle: The Diagonal Pencil Inscription in ''An Island in the Moon''", ''Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly'', 52:1 (2018)

* . "Paper and Watermarks in Blake’s ''An Island in the Moon''", ''Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly'', 52:3 (2019)

* Damon, S. Foster. ''A Blake Dictionary: The Ideas and Symbols of William Blake'' (Hanover: Brown University Press 1988; revised ed. 1988)

* England, Martha W. "The Satiric Blake: Apprenticeship at the Haymarket?", in W. K. Wimsatt

William Kurtz Wimsatt Jr. (November 17, 1907 – December 17, 1975) was an American professor of English, literary theorist, and critic. Wimsatt is often associated with the concept of the intentional fallacy, which he developed with Monroe Beard ...

(ed.), ''Literary Criticism – Idea and Act: The English Institute, 1939–1972'' (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974), 483–505

* Erdman, David V. '' Blake: Prophet Against Empire'' (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1954; 2nd ed. 1969; 3rd ed. 1977; rev. 1988)

* . (ed.) ''The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake'' (New York: Anchor Press, 1965; 2nd ed. 1982)

* Frye, Northrop. '' Fearful Symmetry: A Study of William Blake'' (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1947)

* Gilchrist, Alexander. '' Life of William Blake, "Pictor ignotus". With selections from his poems and other writings'' (London: Macmillan, 1863; 2nd ed. 1880; rpt. New York: Dover Publications, 1998)

* Harper, George Mills. ''The Neoplatonism of William Blake'' (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1961)

* Hilton, Nelson, "Blake's Early Works" in Morris Eaves (ed.) ''The Cambridge Companion to William Blake'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 191–209

* Keynes, Geoffrey. (ed.) ''The Complete Writings of William Blake, with Variant Readings'' (London: Nonesuch Press, 1957; 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1966)

* Kirk, Eugene. "Blake's Menippean ''Island''", ''Philological Quarterly

The ''Philological Quarterly'' is a peer-reviewed academic journal covering research on medieval European and modern literature and culture. It was established in 1922 by Hardin Craig. The inaugural issue of the journal was made available at sixty ...

'', 59:1 (Spring, 1980), 194–215

* Ostriker, Alicia (ed.) ''William Blake: The Complete Poems'' (London: Penguin, 1977)

* Phillips, Michael (ed.) ''Blake's An Island in the Moon'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987)

* Rawlinson, Nick. ''Blake's Comic Vision'' (Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003)

* Sampson, John (ed.) ''The poetical works of William Blake; a new and verbatim text from the manuscript engraved and letterpress originals'' (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1905)

* Shroyer, R. J. "Mr. Jacko 'Knows What Riding Is' in 1785: Dating Blake's ''Island in the Moon''", ''Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly'', 12:2 (Summer, 1979), 250–256

* Stevenson, W. H. (ed.) ''Blake: The Complete Poems'' (Longman Group: Essex, 1971; 2nd ed. Longman: Essex, 1989; 3rd ed. Pearson Education: Essex, 2007)

External links

''An Island in the Moon''

at the

William Blake Archive

The William Blake Archive is a digital humanities project started in 1994, a first version of the website was launched in 1996.{{cite journal, last1=Crawford, first1=Kendal, last2=Levy, first2=Michelle, journal=RIDE: A Review Journal for Digital E ...

''Bartleby.com'' article

* ' ttps://archive.today/20130415164216/http://jhmas.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pdf_extract/1/1/41 A Note on William Blake and John Hunter by Jane M. Oppenheimer, '' Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences'', 1:1 (Spring 1946), 41–45 (subscription needed) *

William Blake and the Lunar Society

by William S. Doxey, ''

Notes and Queries

''Notes and Queries'', also styled ''Notes & Queries'', is a long-running quarterly scholarly journal that publishes short articles related to " English language and literature, lexicography, history, and scholarly antiquarianism".From the inne ...

'', 18:3 (Autumn, 1971), 343 (subscription needed)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Island in the Moon

1784 books

18th-century manuscripts

Unfinished books

William Blake

Satirical books